State of the Industry – Swiss Watchmaking in 2020

A bird's eye view of the landscape.

Morgan Stanley has just published its yearly report on the Swiss watch industry – which is a proxy for the global luxury-watch industry since majority of such watches are made in Switzerland. Put together by the research department covering the luxury-goods sector, the report is always very much anticipated, not only by clients of the bank, but also by top management at many watch brands because it’s regarded as the industry “top 50” list.

It should be noted that Morgan Stanley’s industry report – I contributed to the publication via my consultancy firm LuxeConsult – is based on 2019 sales, therefore the devastating impact of the COVID-19 coronavirus is not included. However, I do discuss the industry outlook in light of the pandemic at the bottom of this article.

To start, some of the key takeaways from the report.

Takeaway 1: Accelerated polarisation

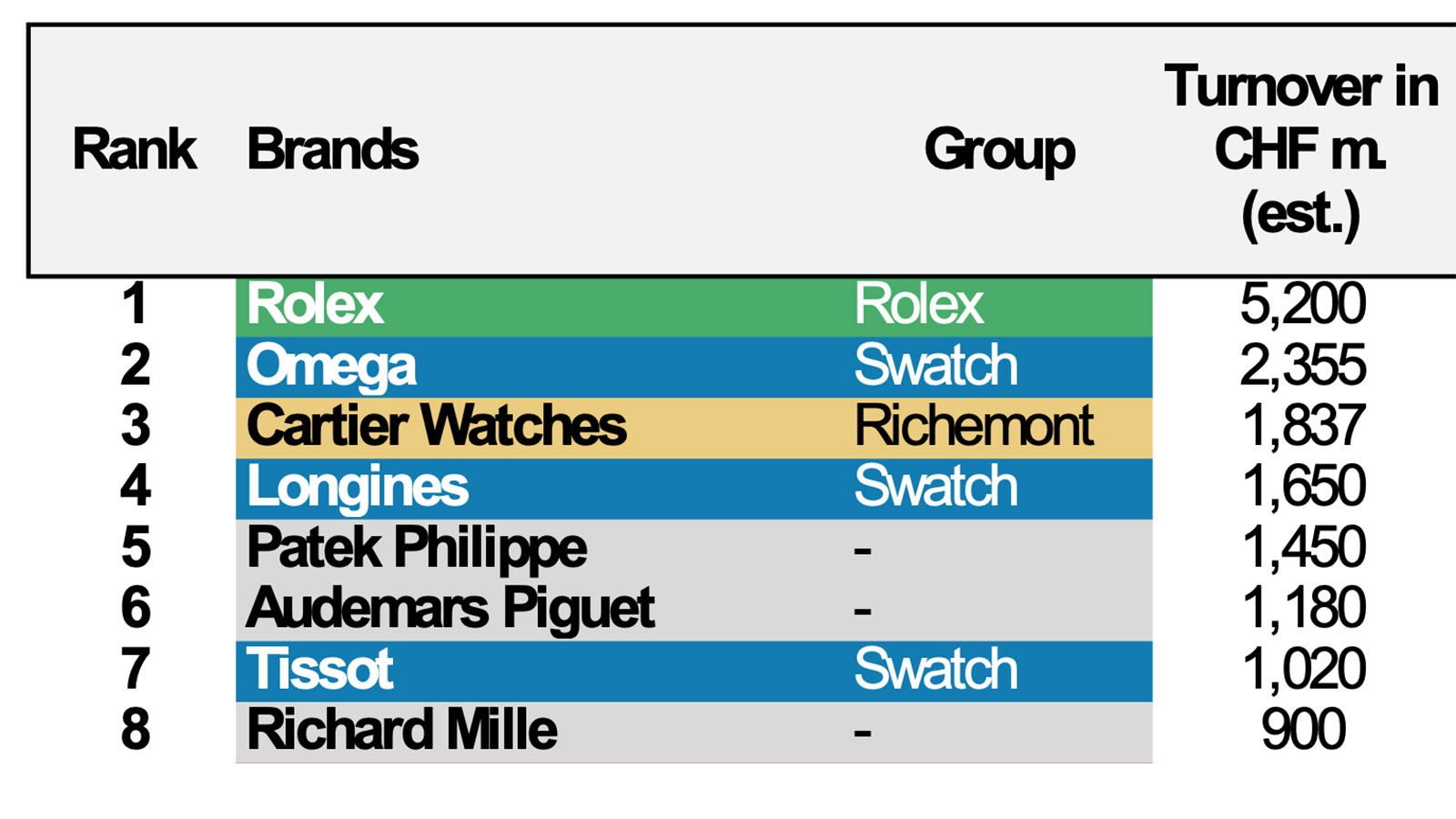

The first industry report, which was published in 2018 and based on the preceding year’s figures, highlighted the fact that only seven brands had sales above the magic, one-billion Swiss francs mark. This concentration hasn’t changed since then, and in fact, we see that the polarisation has further increased – with a few outperforming brands against the vast majority of brands that are either stagnating, or worse, weakening.

The sales ranking is topped by the same seven champions, which are all amongst the 50% of brands (of the top-50 list) that achieved growth last year – with the noticeable exception of Tissot, which dropped to seventh place after losing CHF30m in sales.

Source: LuxeConsult, Morgan Stanley Research

As the table above reveals, there is only one brand that might join the exclusive billionaires’ club in 2020 – Richard Mille.

To avoid any confusion, the sharp rise in the brand’s estimated annual sales, from CHF320m in 2018 to CHF900m last year, is mainly due to the total integration of its retail operations, which now comprise 42 boutiques worldwide with no third-party distribution. Leaving out the uptick from the reorganisation of distribution, Richard Mille’s organic growth was 20%.

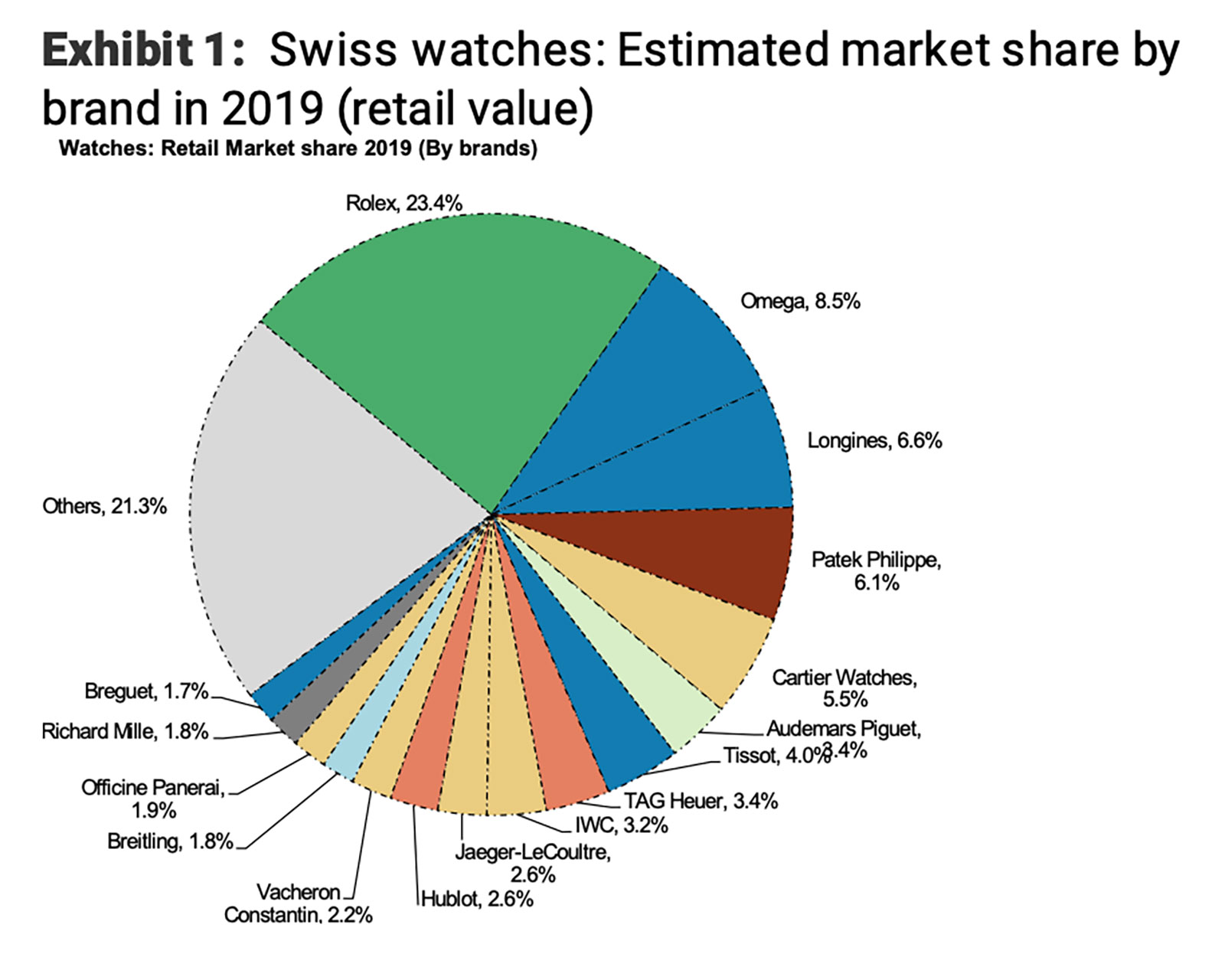

The chart below (based on retail value) illustrates the impressive dominance of one brand: Rolex. It has a share of almost one quarter of the industry total. And its subsidiary brand Tudor is ranked 20th, with an estimated CHF310m in sales and a market share of 1.4%.

Source: LuxeConsult, Morgan Stanley Research

Takeaway 2: Winner takes all for privately-held brands

The watch industry is probably the only segment of the luxury industry where privately-owned brands consistently performing better than listed companies. In contrast, most market leaders in other segments, Hermes and Ferrari for instance, are publicly traded.

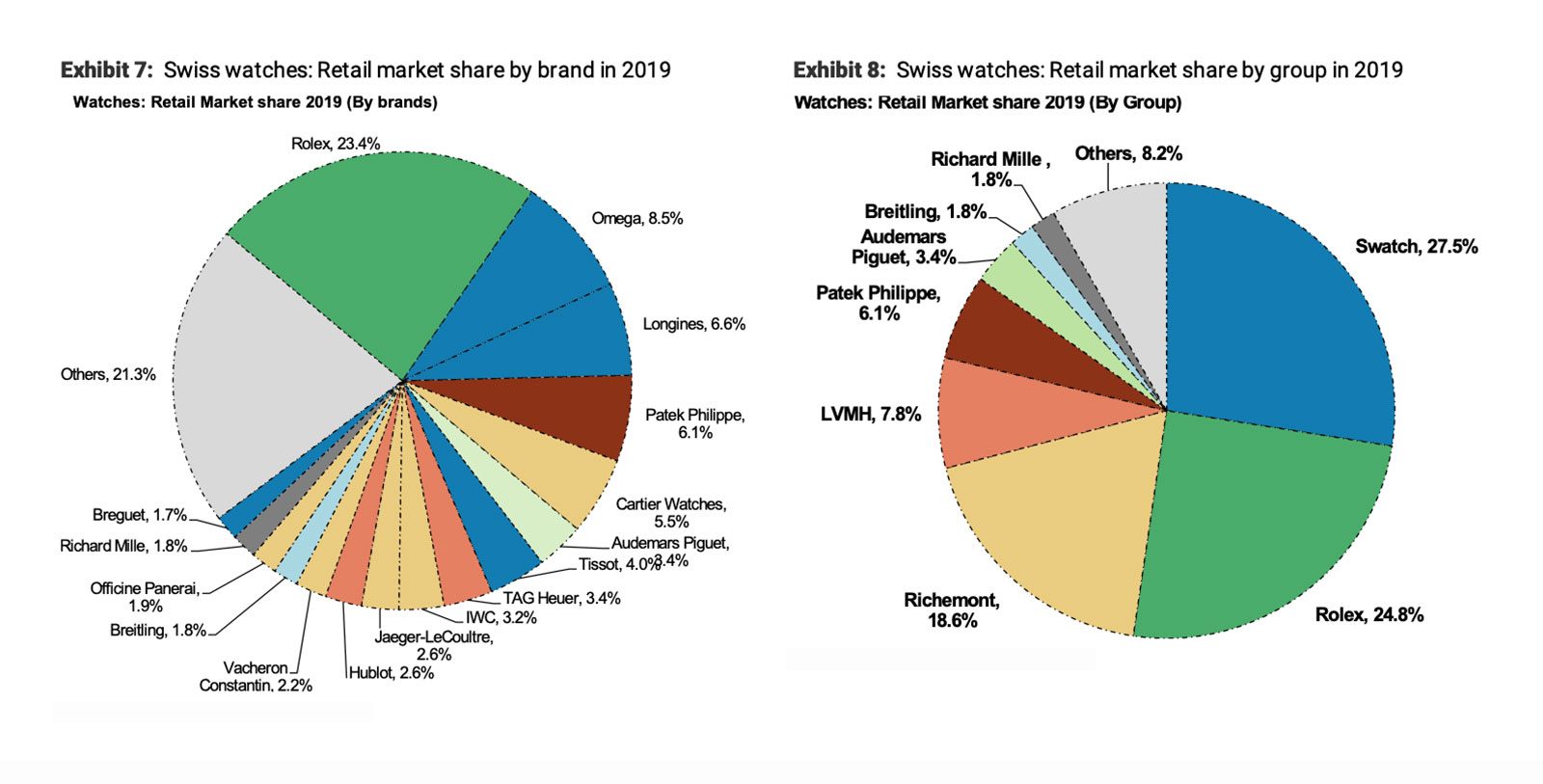

The top four private companies – Rolex, Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet and Richard Mille – had combined sales of CHF8.7 billion, which translates into a combined market share of 35%. Furthermore, these champions achieved their best-ever results in terms of sales and profitability in 2019.

In comparison, the four listed players that each own multiple brands – Swatch Group (17 brands), Richemont (11 brands), LVMH (six brands) and Kering (three brands) – account for 37 brands combined but only have a 55% market share.

Source: LuxeConsult, Morgan Stanley Research

Takeaway 3: Profits are unevenly distributed

We estimate that the Swiss watch industry profit pool amounts to CHF5.3 billion, with a staggering 59% going to the top four privately-held brands. The quartet is growing faster than the industry at large, which translates into an ever-growing market share; and they are also more profitable, with estimated, aggregate operating margin of 35%.

In contrast, the four listed groups – Swatch Group, Richemont, LVMH, and Kering – are left with 39% of the total profit pool. So even though they account for 55% of total sales, their profitability on an individual-brand level is substantially lower than at the privately-owned brands.

So what is left over for the everyone else outside the top-50, which by our estimates is some 300 brands?

Not much – 90% of sales and 98% of the profits are captured by the largest 41 brands (four privately-owned and the 37 brands owned by listed groups).

What’s next?

In a market we estimate to be worth CHF50 billion francs at retail, and which grew by 2.6% according to export data provided by trade body Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry (FH), we can clearly see an industry trying to find its future in ultra-niche and high-end products. The Swiss are still masters of the game at the high-end, with Swiss watches accounted for an estimated 53% of the worldwide watch market by value, but only 2% by volume – meaning the average value of a Swiss watch is far, far higher than watches produced elsewhere.

But even within the Swiss watch industry the mix is changing in favour of the high-end; the industry sold 3m fewer watches in 2019. That’s a 13% decrease from the year before, and the sharpest loss so far, continuing a downward trend that has seen volume decreasing from 30m watches a year at the peak to 20.6m last year.

All of that means a few trends have become clear.

Lose of share at the bottom

The Swiss watch industry should be concerned that it is losing market share in the entry-level and mid-range segments. To quote the late Nicolas G. Hayek, founder of the Swatch Group, who stated in the March-April 1993 issue of Harvard Business Review: “The moment you retreat from a market segment you allow your competitor to move up to the next layer. Then the retreat starts again.”

I couldn’t agree more with that statement. One of the very few noticeable exceptions is the Swatch Group, which owns brands that are strong in those segments. Apart from their brands, almost no one is competing against the newest competitors for Swiss watches – smartwatches, foremost Apple Watch that sold 30m units last year; crowdfunded initiatives by micro-brands; and fashion brands. Eventually someone realise where the market is going and take the lead by becoming the new Swatch watch.

Strong brands propel themselves

Each segment is dominated by a very small number of brands: the mid-range (Longines, Tissot, Tudor), the premium segment (Rolex, Omega, Cartier, IWC, TAG Heuer, Breitling), and the high-end (Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet, Richard Mille). And these strong brands generate a their own positive momentum in a virtuous cycle.

These brands are capable of investing in their marketing and communication, product innovation and development, and retail network integration (with the noticeable exceptions of Rolex and Patek Philippe, which both rely almost exclusively on third-party retailers). This builds demand for their product, which allows them to continue investing.

The rise of micro-segments

Clusters of strong brands create potential micro-segments, beyond the broad segments and brands mentioned above. The market is going to include the following micro-segments:

- Artisanal brands producing extremely low quantities of watches, sometimes below 50 pieces a year, relying on artisanal techniques: Instead of third-party retailers, they sell mostly direct to discerning watch collectors around the world and thus optimise margins. Such brands are the epitome of luxury – rarity. The most successful examples here are Voutilainen, Akrivia, and De Bethune.

- Micro-brands with an appealing story linked to a very specific territory: MB&F and its founder Max Büsser, for instance, has created a unique practice of collaborating with some artisanal brands, and launches a new watch each year that is limited in production, without having a permanent product offering.

- Crowd-funded and crowd-sourced initiatives:

- The best recent example being Code41, which started with total transparency on sourcing and margins. The brand was open with the origin of each component, and did not hide the fact that the case, for instance, came from China. Its most recent initiative. and in my opinion the most interesting, was the launch of a new watch that was crowd-funded, but also crowd-sourced via a community of aficionados who could vote on each step of the design process. And movement, which represents 87.5% of the whole production cost, is entirely made in Switzerland but not a mainstream movement from ETA but made by a small specialist, Timeless. Needless to say, they sold out in record time and had to do additional production runs to fulfil the demand.

- Another example is Daniel Wellington, which was not driven by overwhelmingly wide product offering, but by a social media strategy that targeted millennials. Launched in 2011, the brand got to 2.5m units by 2018, which translated into US$250m in sales and an operating margin that would the envy of any luxury brand.

- Why can a Swiss brand not do the same? SevenFriday, for instance, was a good concept, but it is not Swiss made.

- Fashion brands: By extending their product offering, such brands offer watches at a low price point corresponding to the brand’s positioning, which are seen as a fashion accessory. Calvin Klein, Guess and Diesel are good examples of this strategy.

I sincerely hope that 2020 is going to end up a lot better than it started, but nevertheless I expect all brands to suffer in varying degrees, and 30 to 60 Swiss-made brands to disappear.

The human tragedy of the COVID-19 coronavirus will have two positive effects on our industry. It will compel the industry to rethink its dependency on a single market, and also question the reality of too many ostensibly Swiss-made brands being overly reliant on Chinese-made products.

A 20-year veteran of the industry, Oliver R. Müller is the founder of boutique consultancy LuxeConsult. After having worked at brands like Omega and Chopard, Oliver became an entrepreneur and amongst other roles, was the founding chief executive of independent brand Laurent Ferrier.

Back to top.